The Dilettante's Dilemma

Getting airlifted off of Mount Stupid

Mountain-Climbing: A Metaphor

Mountain-climbing stimulates all of your senses: the wind chaps your skin as it cuts across your face, the air contains both the smell and taste of earthy freshness, squirrels scurry around in the fallen leaves producing the noise of an animal that should be 50 times its size, and lastly, once atop the mountain, you can see the splendidness of the surrounding landscape for miles in all directions. It is this last sense, the sense of sight, that propels me to climb mountains; the view from the peak is what I seek.

After reaching the summit, however, I never hike back down through the mountain's valley. Instead, I am airlifted via helicopter off the mountain top, and dropped off at the base of a different mountain where I begin climbing anew.

When I explain this approach to mountain-climbing, other people often respond critically. They tell me that getting airlifted off of every mountaintop is a huge waste of time, effort, and resources.

The Perks of Being a Dilettante

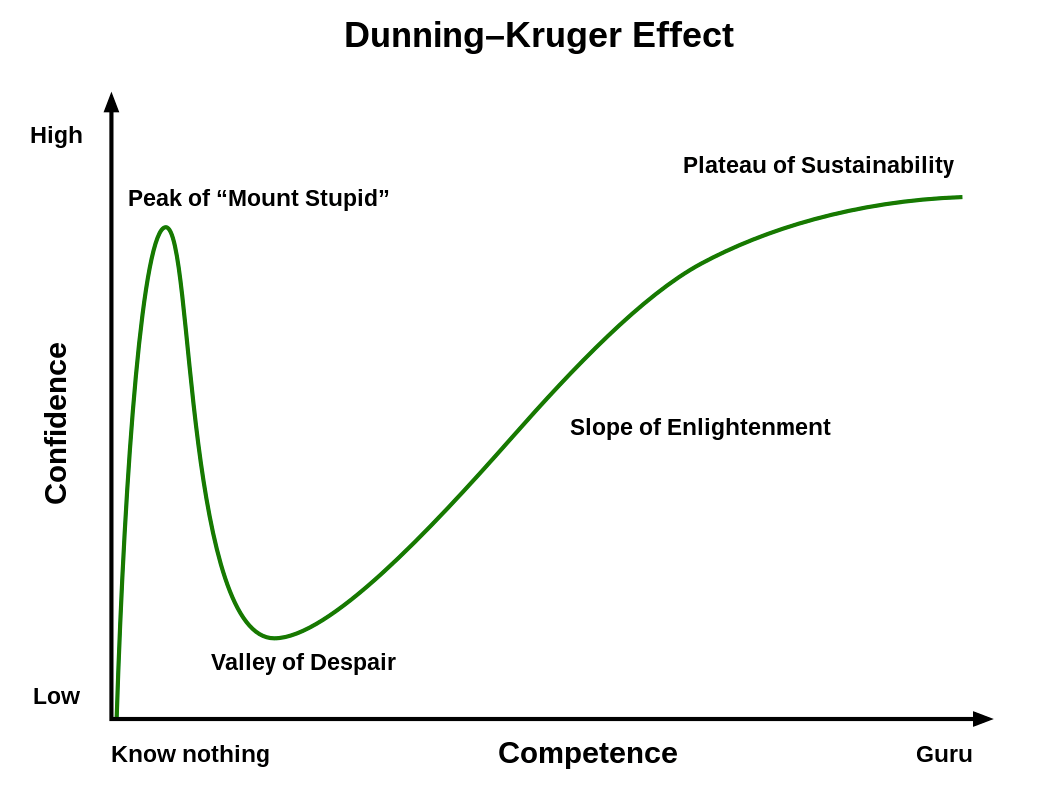

Now, I have never actually been airlifted off a mountaintop, and I really don't mountain-climb as a hobby. What I sketched out above is a metaphor for my approach the dilettante's approach, to accruing knowledge and gaining competency. A graph of the Dunning-Kruger Effect below helps illustrates the point I am trying to make.

A quick explanation of the Dunning-Kruger Effect directly from Wikipedia: The Dunning–Kruger effect is a cognitive bias whereby people with low ability, expertise, or experience regarding a certain type of task or area of knowledge tend to overestimate their ability or knowledge.

In any given field, be it scientific or artistic, the dilettante learns just enough information about the subject to reach the Peak of Mount Stupid, as illustrated in the Dunning-Kruger Effect graphic above. Atop Mount Stupid, the dilettante enjoys several perks, including:

- The intoxicating feeling of superiority by having slightly more information on some arcane subject than his or her (but probably his) friends and family members.

- The nearly unlimited access to more peaks of Mount Stupid afforded by (or caused by) the frictionless Internet.

- Lastly, a wallet full of $5 and $10 gift cards to local bars for coming in third place on trivia night. (An aside: Dilettante's tend to not win in trivia contests. Often, they'll believe they know the answer to most trivia questions, but upon finding out they answered incorrectly, they'll exclaim, "Oh, I knew that. That question was just poorly phrased." The dilettante goes to great lengths to rationalize his spot atop Mount Stupid, all while ensuring his ego remains intact.)

The Dilemma

What does a dilettante do when he or she (again, probably he) finally discovers that he is suffering from "dilettantism"? Does he acknowledge his wayward approach and pivot to becoming an expert in something? Or does he lean into his epistemological shallowness?

Specialization has its rewards. Namely monetary. For example, in May 2021, the median Programmer earned $93,000 in the US, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Dilettante's don't know Python or JavaScript, and rely heavily on google searches to get through simple Excel spreadsheets. But, they are high on all of those squishy, unquantifiable soft skills appended to the base of a résumé like "Communication," "Leadership," and "Professional Presentations". And often, their compensation reflects this lack of expertise.

So shouldn't the dilettante stop summiting Mount Stupids and start specializing?

Answer: Who would want to hike back down through the "Valley of Despair"? That sounds not so fun.

Instead what I've done the dilettante does, is start a blog and hope that something positive materializes from his ultracrepidarian (look it up) ways.